Comparison of Oak Adjuncts

Updated 10/27/2022

Winemakers typically want to flavor their red wines, some white wines, and occasionally fruit wines with oak. It’s common to add oak adjuncts (products made of oak specifically for winemaking) to carboys to impart the desired aroma and flavor.

A common question in winemaking is, “What oak product should I use?” There are a lot of choices and for a beginner it may seem like way too many choices. Following is my view on the pluses and minuses of oak adjuncts for both fermentation and bulk aging. I cover the following adjuncts:

- Dust

- Chips

- Cubes

- Staves

- Spirals

- Barrels

First, a quick description of fermentation and aging oak:

- Fermentation Oak: Used during the relatively brief fermentation process, which lasts roughly one week. “Sacrificial” tannin is extracted from the oak, and later precipitates. This protects the preferred grape tannin (there are numerous types of tannin), as the oak tannin precipitates first. As a result this is called “sacrificial tannin”, as it’s sacrificed in place of the grape tannin. Due to the quick nature of fermentation, oak adjuncts with lots of surface area are used.

- Aging Oak: Used during bulk aging to impart flavor and aroma in the wine. As the name indicates, this takes place over a significantly longer time frame than fermentation oak.

Note that oak for aging is typically white oak, commonly French, Hungarian, and American oak. The oak is typically aged 1-1/2 to 3 years before being toasted. Oak is toasted before use, commonly in Light, Medium, Medium-Plus, and Dark levels. I’m not addressing toast level in this post, as it’s a separate subject.

Dust

Toasted oak dust (or powder) is typically used as fermentation oak. Due to small particle size, the surface area is tremendously greater than all other oak adjuncts, and the extraction rate of tannin is much greater during the short fermentation cycle. Dust is included in some kits.

When used for aging, dust quickly affects the wine. In addition to plain dust, there are several commercial products designed specifically for flavoring wine post-fermentation, although I have not used them and they are outside the scope of this article.

Chips

Toasted oak chips are of variable size, typically 1/16″ to 1/8″ thick, 1/4″ to 3/4″ wide, and 1/2″ to 1″ long. Chips are used both for fermentation and aging.

Major advantages are that chips are both commonly available and the most inexpensive oak adjunct. They work well for fermentation and aging, and are configurable — it’s easy to adjust the amount added to the wine, and different toast levels and oak types can be mixed at will.

A correspondingly large disadvantage is that unless contained in a muslin bag or other container, the only way to remove them from wine is through racking.

A further issue for me is that the chips are the most variable in size, so figuring out how much chips to use is more difficult. Surface area directly affects extraction of tannin and flavoring from the wood. Note that many winemakers do not consider this as much of an issue as I do.

Cubes

Cubes are typically 1/2″ per side and are relatively uniform, although a bag of cubes will have some “chips”, e.g., smaller pieces from the edges of the larger block from which they were cut. Cubes are typically used for aging, not fermentation, due to the lower surface area in comparison to dust and chips.

The uniformity in size is an advantage from my POV, as 1 oz cubes from different vendors will have roughly the same surface area.

Typically a bit more expensive then chips, other then uniformity in size, cubes have the same advantages and disadvantages — once in a wine, they stay there until I rack.

I purchase cubes by the pound and keep the bag sealed tightly. In general, if kept dry and in a closed package, all oak adjuncts have a very long shelf life.

Note: When I add oak adjuncts to a neutral barrel or carboy, I leave them in for the duration, anything from 3 to 12+ months. Chips and cubes are expended in about 3 months (all oak character is used up), so leaving them in longer makes no difference. So I don’t bother removing them until I rack for a different reason.

Staves

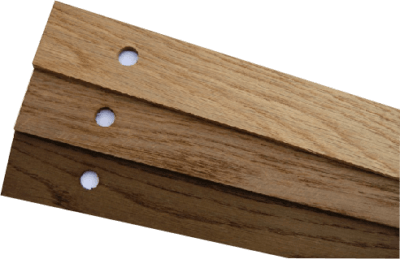

Oak staves are just that — a small oak plank that has been toasted. I’ve noticed some vendors drill a hole near one end, which is handy for retrieving them from the secondary container.

Staves are used for aging — the relatively low surface area makes them less useful for the short fermentation cycle.

The advantages of staves are uniformity of size and ease of use.

Staves of a given size have exactly the same surface area, so the effects on wine can be known and trusted.

Ease of use? The hole allows the winemaker to suspend the stave within the secondary container using nylon fishing line, and wedging the line between the bung or stopper and the container mouth. The stave can easily be withdrawn at any time.

A disadvantage is that the staves are not configurable, e.g., it’s harder to vary the amount used except in adding more staves. Note that stave size can be adjusted with a hacksaw, and a hole can be drilled in the cut-off piece.

Staves are also more expensive than chips and cubes.

Spirals

Spirals are oak cylinders that have a slot cut in a spiral pattern. This produces more surface area than a stave.

As with staves, spirals are used for aging, not fermentation.

Generally speaking, they have the same advantages and disadvantages of staves, e.g., nylon fishing line can be used to suspend them in the secondary container, surface area is uniform, etc.

However, spirals are more configurable than staves, as the spiral can be snapped or cut at whatever point is desired. The spiral nature of the product makes it simple to tie the fishing line in the slot, so it’s not a not of work to make use of smaller pieces.

Spirals are the most expensive oak adjunct.

Barrels

While barrels are not an oak adjunct, they do impart oak character on wine.

My barrels were purchased used (from people I know) and were neutral (oak character used up) long before I purchased them. I wanted neutral barrels as I can fully control the oak character imparted by adding adjuncts. I can add as much or little as I want, mix oak types, and leave the wine in the barrel as long as desired without worrying about over-oaking the wine.

Over-oaking is a strong consideration with new barrels, especially small barrels. Full size barrels (~60 US gallons) can hold wine for years. As the barrels get smaller, the interior surface area vs. barrel volume increases, and very small barrels can be used to contain a batch for only a matter of months, or even weeks.

This section is a caution for folks purchasing barrels — research the topic before buying one.

Conclusions

All oak adjuncts do the intended job. Consider the advantages and disadvantages of each, and try whatever seems to be the best choice, or try several to see which you favor.

3 Responses

[…] Oak also helps impart more body and preserve color, so red wines fermented with oak have more color. Here is a comparison of oak adjuncts. […]

[…] addressed the topic of oak adjunct types in a different post. I suggest you read that one before continuing with this […]

[…] my post Comparison of Oak Adjuncts I present my understand of oak used in […]